Rejuve Community Asks: What Lessons Can Be Learned from Blue Zones?

- Hussein Elwan

- Mar 11, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: May 1, 2024

Our Rejuve community is one of the most active and passionate longevity collectives out there. There’s never a dull moment, and fascinating topics always pop up across our social channels. That’s why we recently decided to take some of these discussions to the blog and let the whole world partake.

Following our recent dive into a groundbreaking intersection of AI and medicine, we shift gears to explore a topic that’s markedly different yet equally captivating: Blue Zones.

The question that sparked this exploration came from our community member, David Ludwick, on Telegram, asking, “What lessons on longevity can be learned from the blue zones and incorporated into Rejuve?”. That’s a good one, David!

For those new to the concept, “Blue Zones” refers to regions around the globe where people live significantly longer lives, often reaching 100 years at rates much higher than the global average. These areas, which include Ikaria in Greece, Sardinia in Italy, Okinawa in Japan, Nicoya in Costa Rica, and Loma Linda in California, are not only geographically and culturally diverse but also rich in lessons about longevity [1].

Indeed, the lifestyles of Blue Zones inhabitants, rather than their genetics alone, play a crucial role in their extreme longevity.

Yet, since there are enough insights about Blue Zone lifestyles to fill an entire Netflix series, today we’re zeroing in on an underappreciated driver of their successful aging: effective coping strategies to manage stress [2].

Through the lens of centenarian data from Blue Zones and beyond, we aim to understand why mastering the art of coping is not just a survival skill but a cornerstone of a life well-lived. But first, let’s have a quick overview of stress and its impact on longevity.

Understanding Stress

Stress is a constant in human life, significantly affecting our health and how long we live. Stress triggers the body’s “fight or flight” response, releasing hormones like cortisol and adrenaline.

Chronic stress specifically can lead to an overproduction of these hormones, causing harmful effects such as inflammation, heart disease, and a weakened immune system. To put that into perspective, it’s estimated that 85% of primary care visits are linked to conditions exacerbated by stress [3].

Research from Yale University has shown that chronic stress can even impact our DNA, speeding up the aging process and potentially cutting our lives short. This kind of stress makes us more susceptible to serious health problems, such as heart attacks and diabetes [4].

Further insights come from a study by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, which highlights the severe consequences of stress on life expectancy, suggesting that heavy stress could reduce it by 2.8 years. For comparison, the same study points out that a lack of exercise can also reduce life expectancy for 30-year-old men by 2.4 years [5].

Beyond just affecting how long we live, stress also influences our biological age — essentially, how old our bodies are on the inside. This measure reflects our overall health and is affected by our lifestyle.

Chronic stress can increase our biological age, indicating worse health. However, the good news from research published in Cell Metabolism is that our bodies have a fantastic capacity to bounce back and reverse the rise in biological age caused by stress [6].

This is exactly where stress management strategies like coping come in.

Understanding Coping

Coping, in psychological terms, refers to the cognitive and behavioral efforts made to manage the internal and external demands of situations that are seen as stressful. It’s intrinsically linked to stress, as it’s among the processes through which we adapt to stressors.

There are two primary models that provide a comprehensive understanding of coping strategies:

The first model categorizes coping strategies into four types [7]:

Problem-focused Coping: Involves taking active steps to directly address the source of your stress.

Emotion-focused Coping: Involves managing your emotional response to stress rather than addressing its source.

Meaning-focused Coping: Involves drawing on your beliefs and values to find purpose, which can help you adapt to stressful situations.

Social Coping: Involves seeking help from others, either in the form of emotional support, advice, or tangible assistance.

The second model suggests that coping with stress involves oscillating between two processes of coping [8]:

Assimilative Coping: Active efforts to shape one’s environment to fit personal needs, often used when stressors are controllable.

Accommodative Coping: Adapting personal goals to align with reality, typically used when stressors are uncontrollable.

It’s important to note that these two models are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary.

The four-category model provides a broad framework for understanding the different coping strategies we use to manage stress. The dual process model, on the other hand, provides a dynamic perspective on how we toggle between two modes of coping in response to different aspects of a stressor.

Regardless of the model employed, a balanced coping repertoire remains key for healthy aging [9] and longevity. In a study on Japanese adults, it was even found that certain coping strategies were associated with lower all-cause mortality rates.

Stress and Coping Trajectories across the Lifespan

The nature of stress we face can vary widely, from the collective impact of sociohistorical events to the personal stresses tied to specific life stages and social roles.

So, exploring this trajectory of stress as we age helps us understand how our coping strategies develop, influenced by a mix of neurological development, social contexts, and individual experiences.

In early childhood, problem-focused coping strategies are fundamentally linked to brain development, particularly in areas that govern executive function [10].

As for emotional coping, young children initially lean on their caregivers to lead the way, gradually gaining the capacity for independent emotional regulation through cognitive strategies as they grow. This shift from external to internal coping mechanisms is a vital developmental milestone [10].

Accordingly, as individuals advance into adulthood, they may deploy more sophisticated, nuanced coping strategies compared to their younger counterparts. Particularly in managing interpersonal conflicts, older adults appear to have an edge in emotional regulation, possibly reflecting a lifetime’s accumulation of coping experiences and emotional wisdom [10].

Given the remarkable longevity of individuals in Blue Zones worldwide, it stands to reason that they have honed exceptionally unique coping footprints across their lifespans, especially given that centenarians score significantly less on stress than younger age groups [11].

Next, we’ll delve into these remarkable coping strategies, uncovering the lessons to be learned from the enduring resilience of the world’s longest-lived people.

Coping Lessons from Blue Zones and Centenarians

Blue Zone centenarians have lived through significant events such as World Wars and the COVID-19 pandemic. Their lives were surely not free from challenges.

However, longevity for them didn’t come from avoiding stress but from handling it effectively. Researchers suggest looking at the life events centenarians have faced to understand their longevity [12]. Surprisingly, 85% of the centenarians in one study viewed their lives positively, despite their hardships [13].

Prof. Belle Boone Beard described centenarians’ coping-empowered outlook to life as, “They looked on the bright side of everything, putting aside temporary inconveniences, refusing to dwell on tragedies or fears, and always considering the better tomorrow.” [14]

So, which coping strategies from the ones we discussed were most likely to be utilized by centenarians? Studies have pinpointed meaning-focused coping as a prevalent strategy among centenarians. Specifically, they tend “not to worry,” “to rely on religious beliefs,” “to take things a day at a time,” and “to accept” health issues [15].

If we zoom in on one of the Blue Zones, researchers described many Okinawan centenarians as possessing high levels of resourcefulness in coping, expressed by “self-confidence, independence, and strength of will” [16].

Speaking of will, Jeanne Calment, who lived to 122, attributed her long life to her strong will, stating, “I had a hell of a lot of will power! A hell of a will power, you understand? And it was very useful to me” [17].

Last but not least, creative arts and self-expression appear to be anchors of centenarians’ coping strategies. Numerous instances illustrate how they navigate through personal challenges by engaging in activities such as poetry and storytelling [18]. These activities allow them to draw from and share their rich personal histories and experiences, shaping their identities in the twilight years of their lives.

How Rejuve.AI Applies These Lessons

Now, we get to the second part of David’s question about how we harness these lessons as longevity researchers and developers at Rejuve.AI.

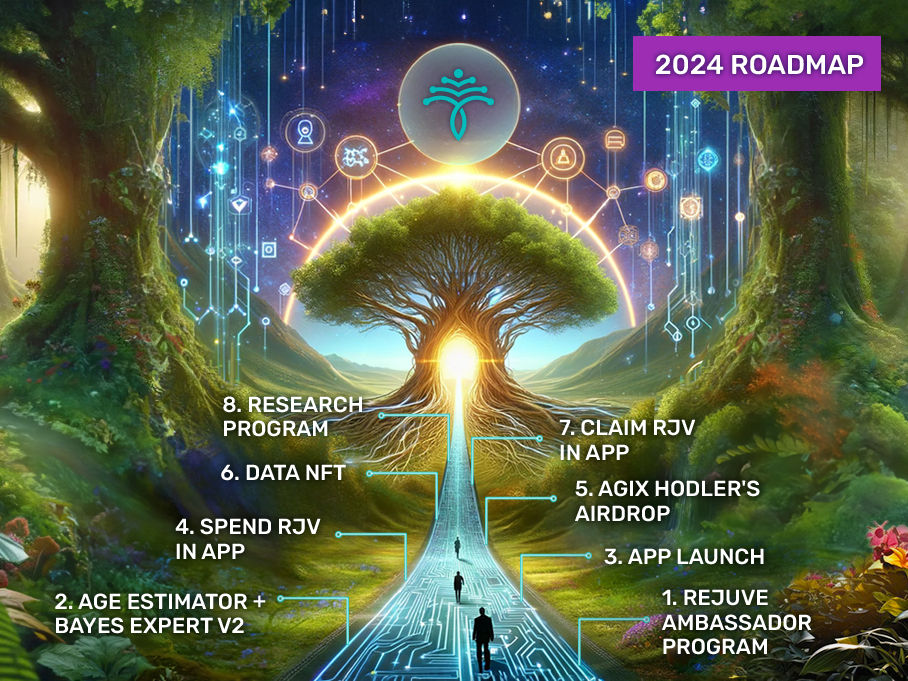

The answer is of course through our first-of-its-kind Longevity App!

Through the App, you can input a wide range of health metrics and track your day-to-day activities — from nutrition to sleep. Simultaneously, our game-changing AI intervenes in two ways. First, it generates an accurate biological age for you based on the progression of the Hallmarks of Aging in your body. Secondly, it provides actionable, evidence-based insights to improve your biological age and, by extension, your health.

A vital aspect of this health equation we focus on is stress. In the app’s Beta version, there’s a special feature dedicated to Vitality, where users record their current emotional state, the amount of time spent on breathwork or meditation, and observe the effects of these practices on indicators like heart rate and blood pressure.

Upon launch, the Longevity App will also feature an expanded Mindfulness chart, giving you a more detailed view of how stress impacts your health and the effectiveness of your coping strategies.

This brings us to the end of our discussion today. Join the conversation and let us know what topics you’d like us to explore next!

Join our Telegram Community

Follow us on Twitter

Connect with us on LinkedIn

Follow us on Instagram

Like us on Facebook

Join our Discord

Subscribe to our YouTube Channel

References:

[1] Buettner, D., & Skemp, S. (2016). Blue Zones: Lessons from the World’s Longest Lived. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 10(5), 318–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827616637066

[2] Martin P. Personality and coping among centenarians. In: Poon LW, Perls T, editors. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics: Biophsychosocial Approaches to Longevity. New York, NY, UK: Springer; 2007. pp. 129–149

[3] Buettner, D. (2012, June 6). 4 Easy Stress Management Strategies | Psychology Today United Kingdom. Www.psychologytoday.com. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/thrive/201206/4-easy-stress-management-strategies

[4] Harvanek, Z. M., Fogelman, N., Xu, K., & Sinha, R. (2021). Psychological and biological resilience modulates the effects of stress on epigenetic aging. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01735-7

[5] Härkänen, T., Kuulasmaa, K., Sares-Jäske, L., Jousilahti, P., Peltonen, M., Borodulin, K., Knekt, P., & Koskinen, S. (2020). Estimating expected life-years and risk factor associations with mortality in Finland: cohort study. BMJ Open, 10(3), e033741. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033741

[6] Poganik, J. R., Zhang, B., Baht, G. S., Tyshkovskiy, A., Deik, A., Kerepesi, C., Yim, S. H., Lu, A. T., Haghani, A., Gong, T., Hedman, A. M., Andolf, E., Pershagen, G., Almqvist, C., Clish, C. B., Horvath, S., White, J. P., & Gladyshev, V. N. (2023). Biological age is increased by stress and restored upon recovery. Cell Metabolism, S1550–4131(23)000931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.03.015

[7] Algorani, E. B., & Gupta, V. (2023, April 24). Coping Mechanisms. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559031/

[8] Jochen Brandtstädter. (2015). Adaptive Resources of the Aging Self: Assimilative and Accommodative Modes of Coping. Springer EBooks, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-080-3_129-1

[9] Uittenhove, K., Jopp, D. S., Lampraki, C., & Boerner, K. (2023). Coping Patterns in Advanced Old Age: Findings from the Fordham Centenarian Study. Gerontology. https://doi.org/10.1159/000529896

[10] Aldwin, C. (2010). Stress and Coping across the Lifespan. In Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.013.0002

[11] Martin, P. (2002). Individual and social resources predicting well-being and functioning in the later years: Conceptual models, research and practice. Ageing International, 27(2), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-002-1000-6

[12] Martin, P., Raiser, V. M., & Poon, L. W. (1999). Significant events in the lives of centenarians. Geronto Geriatrics, 2, 5–19.

[13] Lehr, U. (1991). [Centenarian — a contribution to longevity research]. Zeitschrift Fur Gerontologie, 24(5), 227–232. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1957533/

[14] Beard, B. B. (1991). Centenarians: The New Generation. In Google Books. Bloomsbury Academic. https://books.google.com.eg/books/about/Centenarians.html?id=nxDDEAAAQBAJ

[15] Martin, P., Poon, L. W., Clayton, G. M., Lee, H. S., Fulks, J. S., & Johnson, M. A. (1992). Personality, Life Events and Coping in the Oldest-Old. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 34(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.2190/2am4-7gtq-nj46-9j1x

[16] Willcox, B. J. (2001). The Okinawa Program: How the World’s Longest-lived People Achieve Everlasting Health — and how You Can Too. In Google Books. Clarkson Potter. https://books.google.com.eg/books/about/The_Okinawa_Program.html?id=iDZePgAACAAJ

[17] Allard, M., Lèbre, V., & Robine, J.-M. (1998). Jeanne Calment: From Van Gogh’s Time to Ours, 122 Extraordinary Years. In Google Books. W.H. Freeman. https://books.google.com.eg/books/about/Jeanne_Calment.html?id=W51GAAAAMAAJ

[18] Poon, L. W., Clayton, G. M., & Martin, P. (1991). In her own words: Cecilia Payne Grove. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 15(1), 67–68.